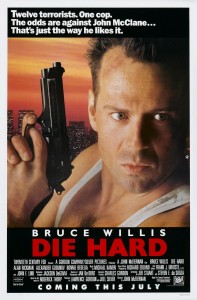

As far as Christmas parties go, Nakatomi Plaza '88 promised to be a raucous night of boozing, cocaine and interoffice sexcapades. That is (record scratch), until Hans Gruber and his merry band of evildoers storm the building and hold it hostage for a king's sum. But they missed one important fact: Nakatomi exec Holly Gennaro's married to one tough NY cop, and he picked the right night for a visit.

John McTiernan's Die Hard earned its clichés the hard way, if you could even call them clichés back in 1988. It seems trivial even pointing this out, but a tight script, brilliant direction and star-cementing lead performance are practically overlooked in retrospect on account of just how rigorously ingrained the film's become to popular consciousness. We all know this film they call Die Hard, and we know it to be good. But it's not just good. It's really fucking good.

Die Hard cemented Bruce Willis as an action star on the level of Stallone and Schwarzenegger; the three men shilling side-by-side for Planet Hollywood in the early 90s further established Willis on the same pedestal as the other two. Rambo is even alluded to in Die Hard when big bad Hans Gruber (introducing Alan Rickman, think about that for a moment) compares McClane to the 80s action hero. But Stallone and Schwarzenegger should probably look at Willis' turn as McClane with some sentiment of despair, because John subverted the battle-tested action hero template of the time, establishing a tone and archetype still reverberating if not outright commonplace today.

McClane works like a rejection of muscled-out killing machines like John Rambo, John Matrix or even The Terminator (literally a muscled-out killing machine). John McClane shoots foreigners with machine guns and spouts one-liners, but that's about where the similarities end. Actually, Die Hard arrived at a time when Hollywood was ready move away from the Cold War as fertile action ground. (It's no coincidence that Lethal Weapon had arrived not long before, and indeed the villains in this film have already rejected the Cold War cause). In truth, McClane has more in common with the cowboys of old — grizzled gunslingers like John Wayne or Gary Cooper to name a few — dudes who weren't one men armies. These dudes of action played fallible characters with weaknesses and elements decidedly more human. Willis's wiry frame and bruised, battered physique suggest stakes in and of themselves. When this guy gets hit with a bullet it's going to hurt.

McClane works like a rejection of muscled-out killing machines like John Rambo, John Matrix or even The Terminator (literally a muscled-out killing machine). John McClane shoots foreigners with machine guns and spouts one-liners, but that's about where the similarities end. Actually, Die Hard arrived at a time when Hollywood was ready move away from the Cold War as fertile action ground. (It's no coincidence that Lethal Weapon had arrived not long before, and indeed the villains in this film have already rejected the Cold War cause). In truth, McClane has more in common with the cowboys of old — grizzled gunslingers like John Wayne or Gary Cooper to name a few — dudes who weren't one men armies. These dudes of action played fallible characters with weaknesses and elements decidedly more human. Willis's wiry frame and bruised, battered physique suggest stakes in and of themselves. When this guy gets hit with a bullet it's going to hurt.

A character like McClane shifts the lens, if only slightly. Audiences are no longer just watching characters dolling out bloody justice, they're empathizing and identifying with the character dispensing said punishment. Characters liked Rambo (starting with First Blood II) represented a fantasy not present in McClane. We project ourselves (men at least) onto Rambo because the majority of us will never be that muscular or wield a Gatling gun. McClane represents something more tangible; a hero with a bad back and broken marriage, someone you could see yourself grabbing a beer with: a paradigm shift towards a sleeker, more sensitive protagonist.

These are just broad strokes, and the truth is that McClane the character doesn't mean shit unless Die Hard the movie isn't equally meaningful. McTiernan had just come from working with Schwarzenegger on Predator in '87; Die Hard has nothing in common thematically even as it reinforces the filmmaker as a leader in the genre. In tandem with a script that passed through the hands of screenwriting titans Steven de Souza and Jeb Stuart, you have a movie that rocks some serious shit.

There's a reason many a screenwriting professor look to Die Hard as a shining example of the craft. Consider the opening scene with McClane in flight: that lingering shot on John's wedding ring, the "balling toes" exposition, the gun hanging underneath his sweater and even the big red bow on the bear. In a brief two-minute sequence we learn John McClane's married, he's traveling, he's a cop distrustful of new surroundings and, most importantly, it's Christmas. The bear's a brilliant touch as Los Angeles is a difficult setting to convey the season.

The following scene with Argyle, McClane's limo driver, brings us up to speed the rest of the way, so much so that it feels as if we're coming into a story and history that's been rolling since before credits. Die Hard is choc full of great character beats, but McClane sitting in the front seat of the limo is among my favorites. It's so tonally consistent to what little we've learned and further establishes our hero as displaced. McTiernan's early external shots work to the same affect, shooting in the very alien-looking "magic hour" between the end of day and beginning of night. It's the kind of brilliant setup that informs an entire film long after it's seeped into your subconscious.

Nakatomi Plaza becomes a character in and of itself, all future-deco supplanted by seven unfinished floors of gun battles. A building run entirely on computers, where characters are asked to use touchscreens? What demonry is this? It's as alien to McClane as it is to the viewer, embellishing on the film's fish-out-of-water identity.

McTiernan spoke years later about shifting the villains from terrorists (Die Hard is a loose adaptation to Roderick Thorp's novel Nothing Lasts Forever) to heisters. The Die Hard films are sort of known for the whole McClane-fighting-terrorists thing, yet it's a misnomer. The antagonists of the series are never peddling terror, though they admittedly use it as a tool. These are bad guys with dollar signs or revenge on their minds, their motivations only thinly political.

This is no truer than for Rickman's Hans Gruber, quite possibly one of the greatest onscreen villains in cinema. The actor had already established himself in theatre and on British television, though this was his first foray into American cinema. It's an inspired performance, over the top in all the right places yet purposefully reigned in when necessary. His educated-German accent is the sort of nuance that's either missing outright or overacted to the point of parody nowadays. He's the sort of bad guy who, clinging to a woman's arm as he's about to fall to his death, attempts to shoot that woman in the head. That's just evil, the best kind of evil.

Perhaps its fitting that influences aren't confined to the same subject matters of its predecessors. Run-and-gun action games like Contra seem like an apt comparison, but I also find it compelling McClane stalks a few bad guys not dissimilar to antagonists in 80s slasher fare. Consider the scene where McClane's confronted by Tony (blonde German, short-haired counterpoint to brother Karl). McClane spends most of the scene off-camera, setting off machinery to scare and disorient his prey only to appear at the last second and come in for the kill. And then in the next scene? Tony's mutilated body is found with a message scrawled in blood for Gruber — that's some sick shit.

No matter how you choose to approach Die Hard, the enduring franchise that followed owes much of its success to the virtuosity of its first entry. That the series would devolve McClane into an unstoppable killing machine ala Rambo is unfortunate. Still, the influence of McTiernan's effort is felt now more than ever, where vulnerable action heroes like Jason Bourne hold a commanding box office presence. Action, like any genre, is an ever-shifting prospect.

Die Hard is thought of as one of its genre's more influential cornerstones, testament to an action-specific progressiveness that's gone unmatched some 25 years after release.