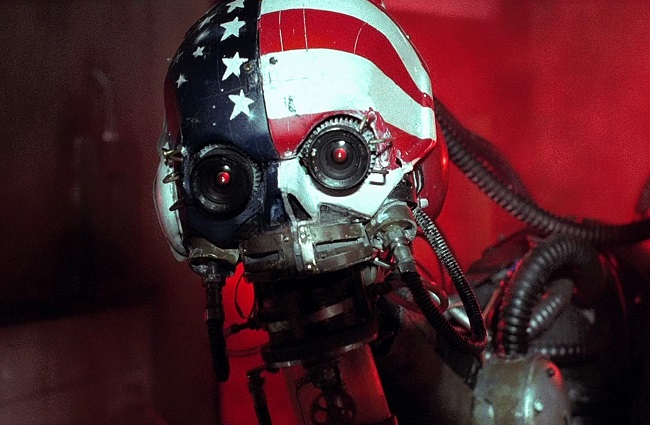

Imagine if The Terminator had Sarah Connor and a T-800 locked in a small apartment for nearly 90 minutes but the T-800 proved too ineffective to ever kill the girl. That's basically the gist of Hardware, Richard Stanley's 1990 sci-fi/horror film that was made with a lot of heart but is often too silly for its own good. The film, which I recall being trumpeted by Fangoria as the next big thing, mostly takes place in one location: the fortified, futuristic living quarters of an unemployed artist named Jill (Stacey Travis). Like everyone else, Jill is just trying to make her way in a run-down but overpopulated post-apocalyptic world. Her soldier boyfriend Moses (Dylan McDermott, who apparently hasn't aged a day in 25 years) brings her home a neat trinket one day — the head of a robot he bought off a scavenger who found it buried out in the irradiated wastelands. Jill uses electronic scraps to create metal sculptures, and Moses thinks it might make a nice addition to her newest piece. He'd probably be right, if only the head didn't power itself back on and start rebuilding itself into the killing machine it was programmed to be.

From there the movie turns into a cat-and-mouse thriller where the robot — dubbed the M.A.R.K. 13 and designed to thin out the human herd — stalks Jill throughout her building and slaughters anyone who dares get in its way. One of the movie's biggest strengths is Travis, who's definitely game for Hardware's genre excesses. By the end of the movie she's drenched in blood and whaling on the robot with a baseball bat; she makes you believe that she's just gone through hell. Had the movie been better, maybe Travis could have ended up being thought of as a female Bruce Campbell, but unfortunately the plotting is too mindless for the film to leave much of an impact. The robot rebuilds itself by crafting arms out of the power tools Jill uses to make her art. So it's all spinning drills and whirling blades. Killing one skinny twenty-something girl shouldn't be too big of a challenge. Unfortunately, this murder machine is fairly awful at murder.

It also disappears for large portions of the film. At one point, it somehow slips outside of Jill's apartment and hides near a window waiting to strike. (Is this really the robot's best plan?) Lucky for it, Jill's degenerate, peeping-tom neighbor (played by William Hootkins — Porkins from Star Wars!) comes over and demands to open up her blinds, giving the kill-bot the perfect opportunity to smash through the glass, surprise the audience and turn someone into bloody pulp. There are only a couple of violent scenes in the movie, but Stanley makes the most out of them, piling on the viscera. No wonder gore-hounds went crazy over this thing 25 years ago.

Despite the nifty blood and guts, however, Hardware is supremely hampered by its small budget. The robot only appears to move via a never-ending series of quick cuts and flashing lights, and I have to assume the on-set prop wasn't very impressive at all. You can't even appreciate it from just a design perspective because Stanley is either unwilling or unable to let the camera hang on the M.A.R.K. 13 for very long. Jill's apartment is a little more effective, what with its steampunk-ish computer terminals and monochrome digital readouts that help give the movie a strong future-ish vibe. There is a vision at play here — one of a dark and grimy universe where the Earth is ruined but too many people continue on trying to play out the string — but the film's localized setting and cheap FX keep it reigned it too tightly. The pacing is also wonky. The movie's first half is far too slow, while its second half feels like it has four different climaxes jammed into it, as the robot is seemingly defeated again and again only to return slasher-movie style for one more attack.

Past that, the movie's just weird. Which can be a boon, especially for horror films of this era. But here the weirdness is kind of a turn-off. There's a sex scene that seems standard until a spying Hootkins starts to narrate the action, turning the whole thing incredibly vile. Lemmy from Motörhead cameos as a taxi driver for no real reason other than to momentarily blare his own music. Iggy Pop plays a radio DJ whose voice is used to establish the universe before he mostly disappears from the film. Stanley throws a lot of stuff at the wall, including a heavy dose of satire, trying to pad out the small-scale story, but not much of it sticks.

Which leaves you with Travis, the gore and a couple of stylistic flourishes (like Moses's trippy near-death hallucinations). In 1990, that was enough to make Hardware a certified big deal, especially when compared to a lot of the dreck that sat beside it on video-store shelves. But watching it today, the film feels like merely a curiosity — a relic of a time when Fangoria was the genre's biggest tastemaker and a modicum of originality coupled with a sprinkle of honest creative passion counted for a lot.